Flattening Groups for ListView

This is the second article in a series exploring some of the technical challenges I encountered while writing my Agenda View Windows Phone app. Last time, I described the grouping features built into the ListView control available to store apps. (My example was a Windows Phone app, but it also applies to Windows 8 apps and Universal apps that run on both phones and tablets.) This built-in functionality wasn’t quite sufficient, because it only works for a single level of grouping, and things go wrong if you try to work around this by nesting some sort of ItemsControl in each item.

It took a couple of iterations to arrive at the solution the app eventually used. This article describes the first attempt. As you’ll see in the fourth article in this series, I ended up needing to refine it a little further, although the same basic idea described in this article still applies.

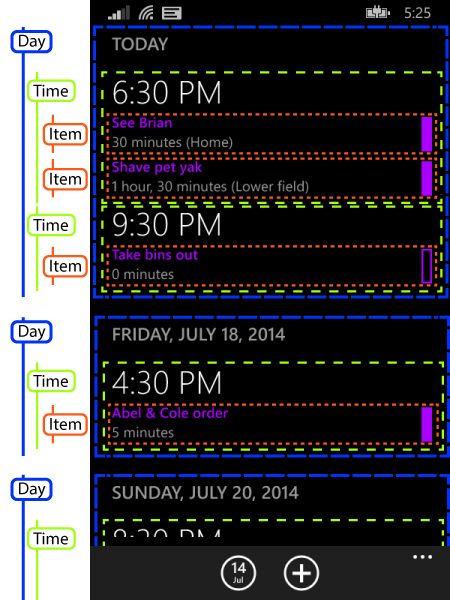

The solution was to avoid using multiple levels of grouping. Now that may not sound like much of a solution, given that nested groups are a non-negotiable requirement. However, all my app really needed was to provide the appearance of multiple levels of grouping. So although the app needs to reflect the logical structure I showed in the previous blog:

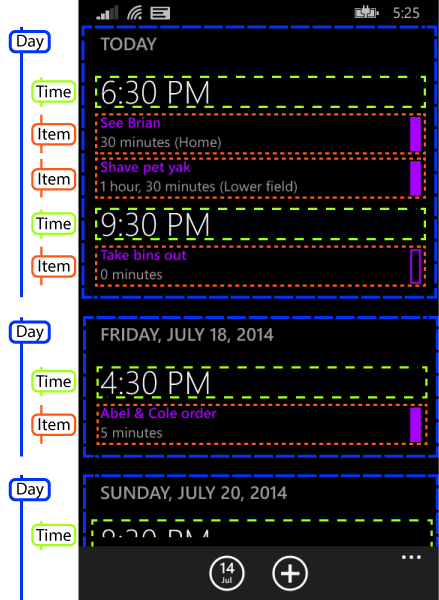

the user will be none the wiser if we implement it with this simpler structure.

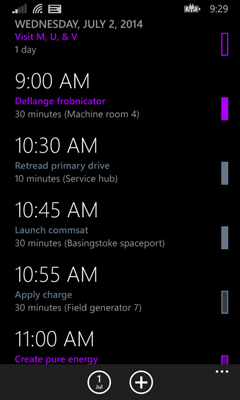

As with last time, the dotted boxes are just annotations I’ve added to a screenshot to illustrate how the areas on screen correspond to objects in the application. Now, we’ve only got one level of grouping—as before there’s a group for each day, but as well as containing items representing time groups, this also contains the individual list items directly.

So although the time groups are present, the ListView does not seem them as groups at all—they’re items just like the ones representing the appointments themselves.

The big change here is that my outer group objects must now provide a heterogeneous list of children. In the context of the town and country examples I used last time, instead of my root collection being a collection of groups, with its definition starting like this:

public class CountryGroup : ObservableCollection<TownGroup>

or being a collection of the underlying items, as I had with my original single-level data:

public class CountryGroup : ObservableCollection<SourceData>

it now needs to be a collection where each item can represent either a town group or an item within a town group. There are a couple of ways to do this. One would be to introduce a new class called something like TownOrGroup (or, if you prefer, ItemViewModel, to make it clear that it’s a type whose purpose is to represent items in the list). The other option is to make the group class derive from ObservableCollection<object>. (Sadly, the CLR doesn’t support additive types, so there’s no native way to represent ‘either a TownGroup or a SourceData’ but that’s what we mean.)

I’ll go with the latter for now. So my country group looks like this:

public class CountryGroup : ObservableCollection<object> { public CountryGroup(IEnumerable<object> items) : base(items) { } public string Country { get; set; } }

My town group is no longer responsible for actually containing the items—it just acts as a header that sits in front of the group. So it now looks like this:

public class TownGroup { public string Town { get; set; } }

The SourceData class representing individual items remains unchanged.

The code to build the data into what look like groups now looks a little different. For each country, we need to generate a single list which contains, for each town group, an item representing the town, and then all the items in that town. No matter how many towns groups there are, we want a single list, so the list might go TownGroup, SourceData, SourceData, TownGroup, SourceData, etc.

While it would be possible to build one big hairy LINQ query to make this, I find it easier to split things up. So to begin with, here’s a method that takes a set of items grouped by town (in the form that a grouped LINQ query would produce) and turns them into a single flat list starting with a TownGroup, followed by all the SourceData objects in that group.

public static IEnumerable<object> ItemsForTownGroup( IGrouping<string, SourceData> townGroup) { object[] groupItemAsList = { new TownGroup { Town = townGroup.Key } }; return groupItemAsList.Concat(townGroup); }

Next, here’s a method that takes all of the items in a country group, groups them by town, runs them through the preceding function to generate a list of items for each town group, and then concatenates all those lists into one big flat list:

public static IEnumerable<object> FlattenedTownGroupsForCountry( IEnumerable<SourceData> countryGroup) { return countryGroup.GroupBy(item => item.Town).SelectMany(ItemsForTownGroup); }

I’ve called the LINQ operators directly because on this occasion I happen to find them easier to read than a LINQ query, but if you prefer that form, this does the same thing:

public static IEnumerable<object> FlattenedTownGroupsForCountry( IEnumerable<SourceData> countryGroup) { return from item in countryGroup group item by item.Town into townGroup from item2 in ItemsForTownGroup(townGroup) select item2; }

Finally, we can use this to populate the country groups:

var countryGroups = from item in SourceData.GetData() group item by item.Country into countryGroup select new CountryGroup(FlattenedTownGroupsForCountry(countryGroup)) { Country = countryGroup.Key }; var cvs = (CollectionViewSource) Resources["src"]; cvs.Source = countryGroups.ToList();

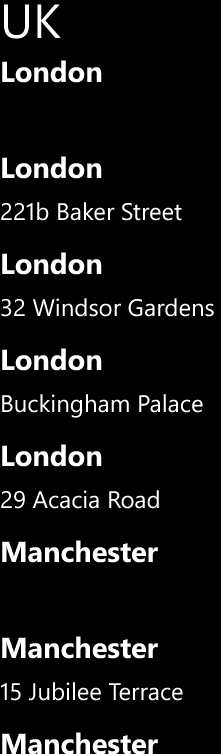

To display this, I can use the same XAML as I did in the first snippet showing a ListView from the previous blog. The result looks like this:

Well that has sort of worked. The structure is exactly right—we have country group headings, and then within that group headings for each town, followed by each of the items in that town. However, this isn’t really how we want to display it—I’m using the same ItemTemplate for every item in the list, which means that it attempts to display headings in exactly the same way as it displays individual items: as a town followed by an address.

For list items that are of type TownGroup, there is no Address property, so we just end up with a blank space for the second row of the item—that’s why there’s a big gap after the first London, and another one after the first Manchester. (If you run this with a debugger attached, you’ll see it complain about data binding failures.) And then for items of type SourceData, we show both the town and address again.

What we really want is to show just the town for TownGroup items, and just the address for SourceData items. One slightly hacky way to do this is to define a new property on both source types with the same name called something like DisplayText that displays whatever we want to use as the text for that item. (Obviously in a real app you’d want to do this in a view model type rather than directly on your underlying model.) And you could even arrange for differences in style by defining a properties to control the font weight and size. So here’s the modified TownGroup:

public class TownGroup { public string Town { get; set; } public string DisplayText { get { return Town; } } public FontWeight Weight { get { return FontWeights.Bold; } } public double FontSize { get { return 24; } } }

And we can add three corresponding properties to SourceData:

public string DisplayText { get { return Address; } } public FontWeight Weight { get { return FontWeights.Normal; } } public double FontSize { get { return 20; } }

We can now use a simpler ListView item template:

<DataTemplate> <TextBlock Height="40" FontWeight="{Binding Weight}" FontSize="{Binding FontSize}" Text="{Binding DisplayText}" /> </DataTemplate>

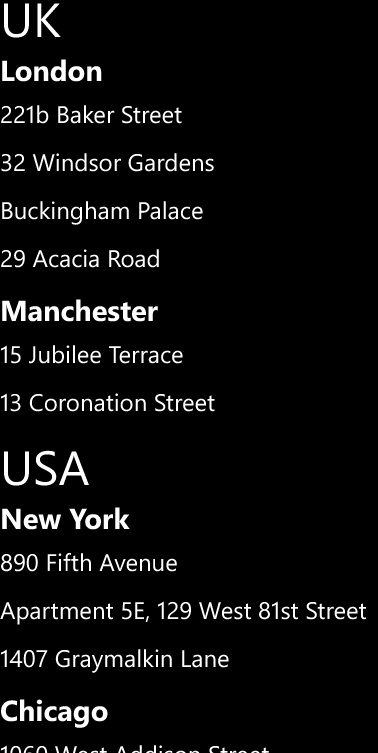

Here’s the result:

That’s now working well. (You can download the project from here. If you try it, you may notice that although the wild layout problems from last time are not apparent, there’s some occasional mild horizontal jiggling. I’ll show how to fix that later in this series.) But we have a problem: the visual distinctions between the town group headers and the individual items are controlled entirely through properties on the data source items. That is likely to be a problem if you want a designer to work on your application, because it means you will have to make code changes to support more or less any visual design change.

Moreover, this technique doesn’t work well if you need headers and items to look significantly different. Going back to my app, you can see that I have exactly that requirement:

Time group headers contain one fairly large piece of text, while individual appointments within a time group contain two lines of text—the appointment subject, and then the duration and location—and also an indicator on the right showing whether the time is marked as busy, out of office, tentative etc.

So, we need to do more. The technique of using heterogeneous list items to make it look like you’ve got multiple levels of grouping is a good one, but we really need some way to enable different element types to have different appearances, without having to add a bunch of ad hoc properties to our source objects. That will be the topic of the next entry in this series.